After combat: World War II, Korea, Iraq

Published 6:01 am Saturday, July 14, 2018

What are the challenges of moving from war zones to the relative safety of American shores? Do choices differ with each individual? Three men tell their stories.

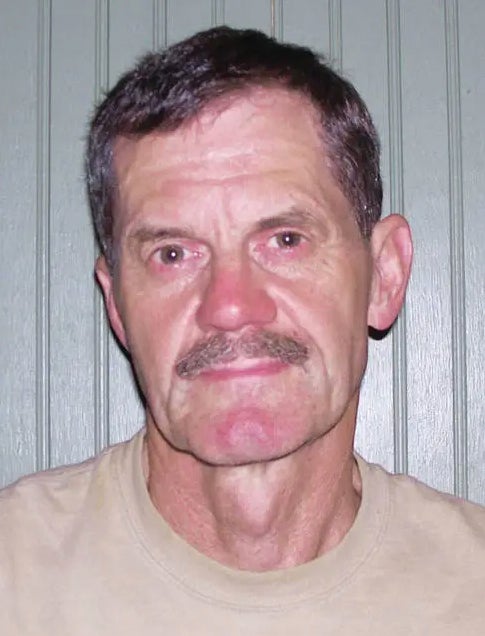

Tagged by journalist Tom Brokaw as a member of the Greatest Generation, Harry Ashburn, a World War II veteran, was a truck driver in the Philippines, occupied by the enemies of America throughout most of the war. At times he was delivering Marines behind enemy lines, but a scene when he was delivering food and other supplies stands out for him. It was following the Great Raid at Cabanatuan Prison on January 30, 1945, where he observed Allied-liberated POWs who were physically challenged, starved, and stoic.

Ashburn exited the Army on November 14, 1945, and returned to his job as a sheet-metal worker for the Pennsylvania Railroad. After two months he, a blue-collar worker from a blue-collar town, decided that college, via the GI Bill, might be a better option. So it was off to Otterbein University where Professor Harold Hancock inspired him to major in history. Ashburn earned his B.A. in 1949, and it was off to a series of teaching, coaching, and administrative positions and an M.A.in administration from Ohio University.

One of his most satisfying positions was his four years at Perry High School in Lima, Ohio, a school with a mix of rural, suburban, and inner-city students. He cites an excellent teacher and coach, Leonard Volbert, as instrumental in the success of that school. Volbert had been “disadvantaged himself and understood students from the ghetto and was able to give them hope, that they could rise out of their economic limitations.” Other faculty were of high quality as well and mentored new faculty in the culture of excellence. Several industries in Lima were willing to supply funds so that as principal Ashburn could bring in inspirational speakers such as Jesse Owens, Olympic Gold Medalist; Wayne Embry, pro basketball player; and William McKinley, Major League baseball umpire.

Ashburn’s longest tenure at 19 years was at Bennett Junior High in Piqua, Ohio, known, according to him, as “a graveyard for principals, a school on the wrong side of the tracks.” Ashburn made it a point to know the names and faces of each of the students from a low of 400 students to a high of 700 within the first six weeks of each school year.

Today, when he meets his former students who say, “You paddled me,” he has the same question for each, “Did you deserve it?” They all say, “Yes.”

He feels that in penalty cases, it’s important that “kids be aware of why they are in that situation.”

And he always gave them options: a regular paddle or the GREAT PADDLE made by the industrial arts teacher and measuring 2 inches thick, 9 inches wide with holes drilled in it, and 2 feet long. No miscreant ever opted for the Great Paddle.

When Ashburn was asked why he retired at age 62 in 1985 from Bennett, he said , “I never got tired of the kids.”

A veteran of the Forgotten War, the Korean Conflict, Benjamin Hiser says of Ashburn, “I never had a son who went to Bennett Junior High who didn’t like him: he is kind, generous, widely respected.”

When Hiser left the U.S. Army in 1953 after serving as a medic and surgical technician in Korea, he had a family to support. With a five-point bonus on the civil service exam for having served in the military and five more points for a service-connected disability, he became a letter carrier for the U.S. Post Office. After 6 years and 9 months of delivering mail, he joined Mid-Continent Properties, Inc., for 14 years and 9 months.

From the time he was first in the military, Hiser had been earning college credits and graduated with a B.A. in history from the University of Dayton in 1977. In that year, he became a full-time student at the U.D. School of Law from which he earned his law degree in 1980.

He attributes his decision to be an attorney to his older brother who had also served in Korea and had a law degree from the University of Arizona. The advice from his brother Harold was that Hiser should go to law school because he’d make more money. This, according to Hiser, was “the only bad advice my brother ever gave me.”

Money was scarce in those early years of practicing law, and Hiser says, “It’s amazing how little you know. Anyone who came in had an issue that required extensive research, and the first time I ever walked into a court room, I was so nervous I almost wet my pants.”

As a member of the Miami County of Ohio’s Public Defender staff, Hiser reports on his most challenging case: A parolee, who had served a lengthy sentence for murdering his mother by beating her to death with a shotgun, was charged with kidnapping and raping a woman. The accuser assumed if the parolee were convicted, he would go to prison for the remainder of his life. The parolee had been violating the terms of his parole by hanging around a bar where he met his accuser, and he and she were driving around southwestern Ohio visiting his former prison buddies when she decided to drive across the state line into Indiana, another parole violation. He objected. She got out of the vehicle and called a former boyfriend and filed the complaint of kidnapping and rape against Hiser’s client.

Prior to trial, Hiser did extensive research of persons with knowledge of the case, and a woman who was to testify on behalf of the accuser hid out in the bathroom on the third floor of the courthouse and wouldn’t come out. The judge sent a bailiff after her. Hiser’s first question when she took the stand was, “Why did you lie?” Hiser won the case, and his client was returned to jail for a short time for parole violation.

Hiser retired from the practice of law at age 72 in August of 2012, and he still misses the camaraderie of those with whom he worked.

The personal dimension of work after combat continues with a decision made by Iraq War veteran, U.S. Army Captain Daniel Hance. A wounded veteran of this war, a war against international terrorism and a response to the 9/11/2001 attacks on U.S. soil, Hance, has determined that he is meant to serve his fellow soldiers and has created The Catalyst Program.

With Post 9/11 benefits covering the cost of tuition, this five-week program provides educational and career opportunities for those leaving the military and is designed to help veterans realize that the leadership skills they learned in the military are transferrable to the civilian world.

College credit is available and those with a bachelor’s degree earn credit toward an MBA. The next program is at Antioch University Midwest in Yellow Springs and runs from October 8 through November 11.

CEO Hance reports that “ The Catalyst Program is designed to help veterans define their skills, their passions, and the opportunities available to them in the business world. Coaching, networking, and job shadowing with superb employment partners are components of the program as attendees develop their brands.”

The web site for the program is TheCatalystProgram.org, and those interested may register at that site.

An educator, an attorney, and a CEO – all three war veterans have important stories. These are men of integrity, of honor, of determination. We thank them for their service, then and now.

Dr. Vivian Blevins is a Harlan County native. She has taught undergraduate and graduate students as well as prison inmates, and now teaches communication and American literature classes at Edison State Community College in Ohio. Reach her at vbblevins@woh.rr.com.