BLEVINS: Still Serving 50 Years Later

Published 4:07 pm Wednesday, January 27, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Vivian Blevins

Columnist

Yes, women serve and have served in the U.S. military. Afterwards, some devote large parts of their lives serving those who have also served.

Judy Johnson of Sidney, Ohio, served in the U.S. Army after graduating from high school in 1970 and currently serves on the Executive Board of American Legion Post 217, on the Shelby County Veterans Commission, Sidney Veterans Honor Guard, and as a volunteer for Miami County Hospice for Veterans.

As a young girl, Johnson says, “I spent a lot of time at the VFW in Piqua, helping with the canteen, assisting with Bingo, and overhearing stories told by veterans to other veterans who had gathered there. Her father, William F. Higgins, was one of them and had served in England in World War II in the U.S. Army as a supply sergeant. Also, he had been a commander of that post in Piqua.

When Johnson went to the recruiting station in Piqua, she was told that she wouldn’t qualify until her braces were removed, so her dentist took care of that issue. She wanted to be a military photographer; however, after she took the written tests and her physical in July of 1970, she learned that her area of expertise had been identified as medical corpsman.

A maternal aunt learned of her activities and said to her, “You know what they say about women who go into the military?”

“No.”

Her aunt declared, “You know that they like women.”

Johnson responded, “I’m not that way. Dad served in the Army, and I want to go to serve my country and for education.”

In 1970, both parents had to sign for women to join the military, and her father said to her mother who was reluctant to sign, “We need to let her go.”

Johnson’s basic training as a WAC (Women’s Army Corps) was at Fort McClellan in Alabama. When she arrived at the base at 7 P.M., tired and hungry, she reports that she was given “a peanut butter sandwich and rotten bananas” and ushered to an open bay area where 60 women were housed with a drill sergeant screaming at 4:30 A.M., “ Get out of them bunks. Police your area. Be in formation at 0500. No talkin’, a—holes.”

Johnson says she thought, Am I really gonna survive all of this?

The standard uniform for a WAC was a skirt with shorts underneath, a blouse, black oxfords, black socks, and a military hat.

Soon she learned to keep her uniform wrinkle free (or be put in the grease pit to wash pots and pans), to take a short shower, to eat all meals quickly, and to not walk on the grass.

She was also introduced to a gas mask in case of nuclear, biological, or chemical warfare and learned first aid, drills and ceremonies, and how to make a tight bunk (At times, she slept under the bunk to avoid having to make it up so that a quarter would bounce on it).

There was no training with weapons as women were slated for administrative, secretarial, or medical duties.

After weeks of keeping the bay area floor looking like glass (WACs rode on the buffer and cut up Army blanket to enhance the shine) and learning to keep the clothes in her foot locker precisely arranged to avoid having everything thrown out by the drill sergeant and requiring to be redone, she was off to Fort Sam Houston, Texas, for eight weeks of training to be a medical corpsman (She learned to give first aid, administer injections, apply tourniquets, and attend to soldiers in combat).

Johnson graduated second in her class and stayed on to become an LPN (Licensed Practical Nurse). For this classification, she learned anatomy and physiology, pharmacology, and did rotations at area hospitals where she sterilized equipment, assisted surgeons, served as circulator (fetching things that were needed), and cared for patients. To learn to debride a wound, class participants were given dead goats.

At Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston, she had her first reckoning with one of the impacts of the war in Vietnam. At 18 years old at the time when the average age of the soldiers in the field in Vietnam was 19, she says, “They had burns. Some were amputees and they had such anger. Four of them told me that if they had their legs back, they would go back to Vietnam and kill the SOB who did that to me.’”

Johnson says, “I’d listen as they described the scenarios, and I was horrified to hear what they had experienced, something that traumatic. I’d go back to the barracks and cry, wondering what their lives were going to be like now.

“The burn and orthopedic units were most eye-opening, but the oncology units were as well.”

In February of 1972, Johnson was reassigned to Fort Benning, Georgia, where she first dealt with the death of one of her patients. The patient, 36, was the spouse of a military man, was in isolation on the second floor of the hospital because of a contagious disease, and had pneumonia. Her husband and children would wave to her from the parking lot that adjoined the hospital, and Johnson says, “I felt sad for the family.”

In her role as LPN, Johnson had to wash and clean her patient’s body, fill out tags for her wrist and toe, fold her arms across her body, wrap her body in a sheet, and transport her to the morgue on the bottom shelf of a special cart that had a black drape across the top with the drape hanging down over the sides and the front and back.

A civilian LPN was assigned to help Johnson, but “She was superstitious about touching the deceased. There was fear in her eyes. I said to her, ‘If that’s the way you’re going to be, I’d rather you leave the room.’” Johnson got a corpsman to help her lift the patient’s body.

She remarks, “With each patient, each death, it’s different. You always remember the initial one.”

Johnson’s military service continued as she married her husband, also in the Army and a Vietnam veteran. She trained in the Army’s AMOSIST program to become a physician extender (certified to give physical exams, treat minor illnesses, and prescribe medications) and saw the WACs become the Army, “genuine soldiers and not pretenders.”

Throughout, she continued to deal with a common belief that if you excelled in the military, it was because you “were giving sexual favors to get promoted.”

Then, in October of 1981, she became a drill sergeant (Remember back when?) at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where she dealt with a gender-integrated training cycle where some women could excel in paper-and-pen testing but had trouble keeping up with the men in physical areas. She also found that some women seemed to have more personal problems that carried over into their military lives. One recruit threatened to use her three live rounds of her M-16 on the firing range to murder Johnson and her assistant. That recruit ended up in CCF (Correctional Custody Facility) and was discharged from the Army.

There were more deployments and promotions, and in August of 1985, Johnson and her husband and their daughter were off to Rhein-Main Air Force Base in Frankfurt, Germany, where a Red Army faction had bombed the base, killing two Americans and injuring 23. At the time, Communists were also suspected of planting explosive devices on the train tracks around Berlin, making essential train travel dangerous.

Because of the threats, Johnson pulled guard duty for a month at the family’s apartment complex, in addition to her assigned work as a ward master on an orthopedic unit and investigator as the senior on-commissioned officer in charge of 10 outlying health clinics.

From the four-year deployment in Germany, Johnson indicates that she learned the following: “(1) to be alert to anything in my surroundings and report it, (2) to value my life, knowing that things can change, and (4) to realize that other places in the world are not as safe as the U.S. was at that time.”

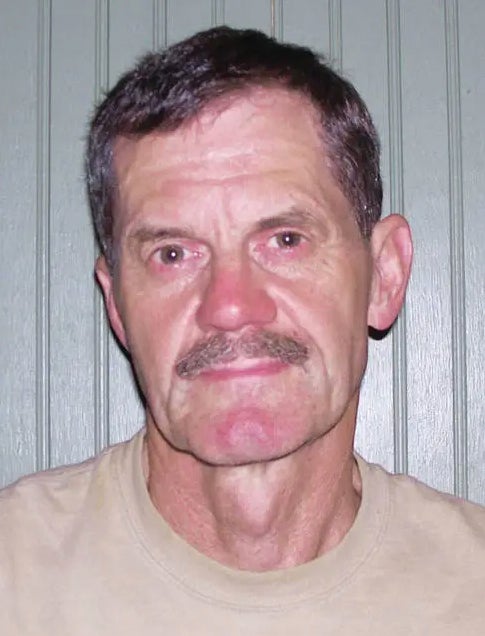

Thank you, Master Sergeant Judy Johnson (Ret) , for your 20 years and one month of active duty, and two years of inactive service in the U.S. Army and for the ways in which you continue to serve our military men and women since that day in July of 1970 when your father said to your mother, “We need to let her go.”